An Exchange Program between Morehouse and Bowdoin Colleges and a Speech by Dr. Martin Luther King that Had a Butterfly Like Influence on the Civil Rights Movement

Martin Luther King accepted an invitation to give a speech at Bowdoin College on May 6, 1964. This was a few months prior to him receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, and a year after he gave the I Have a Dream Speech at the Lincoln Memorial. The speech he gave at Bowdoin College drew an overflow crowd at First Parish Church in Brunswick, Maine. Many observers felt this period was a turning point in getting the Voting Rights bill passed in 1965.

Resonating and applicable today in America, here are a few quotes and points of Dr. King from that 1964 address in Brunswick, Maine.

Regarding the progress in race relations in 1964, he had three points of view.

1) There was extreme optimism that said we all had to just sit down and wait, things will get better.

2) There was an extreme pessimism which stated that there were only minor strides and that integration was impossible.

3) There was a realist attitude that we’ve come a long way, however, but we have a long way to go.

“Segregation is on its death bed. The only question is how costly with the segregationists make the funeral.”

“All sorts of conniving methods are being used to keep Negroes from voting. The difficult question asked of Negros at the polls included: How many bubbles are found in a bar of soap? Well trained lawyers could not answer the legal questions asked. Voters faced physical violence when they seek to register to vote.”

“Segregation is alive in the Juris legal form in the South and in the de facto form in the North.”

“If democracy must live, segregation must die.”

“There must be divine discontent “…about injustice.

“I still have faith in the future.”

“With this faith and with this determination, we will be able to turn the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.”

Bayard Rustin, the organizer of the 1963 March on Washington spoke at Bowdoin College on May 5, 1964, one day before Dr. King.

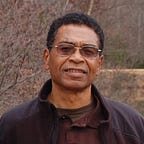

Fred Stoddard, President of Bowdoin’s Political Forum, was surprised when Dr. King and Mr. Rustin accepted an invitation to speak. After the King speech, five of my exchange student classmates from Morehouse and I had the fortunate experience to have a personal audience with Dr. King. In that meeting, he reminded us that we were representatives of Morehouse and Black folks and that we must educate people we meet in Maine about the civil rights movement and the necessity for the people in Maine to understand the significance of it and why they such support the movement. It was inspiring to hear him talk to us personally and give us a strategy to maximize our experience as exchange students in this college in the north. Dr. King was only 35 years old at the time. I was fortunate to be an official Marshall at the March on Washington, where I, in a plaid jacket, stood behind King on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial as he gave the towering I Have a Dream Speech (see photo above). As a Marshall, I worked the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with crowd control and admitting VIPs and celebrities into a reserved area. The March on Washington of 1963 galvanized the civil rights revolution. Dr. King graduated from Morehouse College in 1948 and was mentored by Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays, the president of Morehouse and intellectual father of the civil rights movement.

John Brown Russwurm, was the third African-American to graduate from any college in 1826 at Bowdoin. In 1963 two students, David Bayer and Phil Hansen at Bowdoin College, wrote to Howard Zinn, author of A Peoples History of the United States, who was then a professor at Spelman College, suggesting an exchange program of students from the north to come south and for southern students to come North. Dr. Zinn forwarded this letter to Dr. Benjamin Mays, who agreed to the idea. Pres. James Coles and Dean Leroy Greason, the administrators at Bowdoin also agreed. The first exchange was one week in 1963, where the delegation of Morehouse students spent time talking and meeting people in Maine while a group of Bowdoin students went south for that week to do the same. One of the Morehouse students of that first one-week exchange program was David Satcher, who later became CDC Director and Surgeon General. After the success of this program, it was decided by the two school administrations to make it a semester-long exchange so that there could be more in-depth communication. Also, Bowdoin recognized that they needed to recruit African-American students to diversify their student population, and an exchange program would jumpstart this process. Subsequent to this exchange program African-Americans were recruited in increasing numbers. Ken Chenault, the African-American former CEO of American Express, graduated from Bowdoin in 1973 as a result of these recruitment efforts. I was fortunate to be one of six students in our junior year to be in the semester-long program. We all took the train together in January from Atlanta to Brunswick, Maine. I remember leaving Boston for Maine, and the snow-covered landscape caught my attention as something new to my perspective. At the bus stop in Brunswick, we were met by a delegation that welcomed us to the college.

We first settled in our fraternity houses, which was the dorm system at Bowdoin. My fraternity was Chi Psi, and my roommate was Hardy John Margosian. At the Dean’s office, we participated in a ceremony for signing the matriculation book. All the great personalities from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Robert E. Peary were in this book as graduates of Bowdoin. The big question the administrators posed was whether your name would be blotted out by everyone pointing to the name of a famous person above you. Or maybe you will have a name that everybody points to. Shortly after our arrival, we were invited to a faculty residence for a lobster bake with steamers in the backyard. It was a cuisine extravaganza and a first for me to experience this Maine tradition.

Classes started immediately and along came the mighty snows of New England. I looked out my dorm room window and saw snow coming down for hours as I pondered the thick textbooks of my courses at my desk. I could not believe the intensity of the snow and how long it came down. The outside landscape was a white desert. This was Maine’s weather, the most northern state in the American lower 48. My reactions to the new experience at a new college in the middle of winter were surprisingly smooth and enthusiastic. Everything was new, and I loved the novelty.

A memory that is strong in my initial adapting process to this new environment was the extensive use by students of the library. I remember going after dinner in the fraternity house to the library and not being able to find a seat. I realized that I had to go very early because I had a very heavy load of courses to manage. I loved the challenge that the courses provided, and the professors were excellent.

I learned about the student culture that was prevalent in fraternities in the 1960s. The Beatles made their trip to New York City while I was there, and the entire fraternity house gathered around the TV to watch. Numerous funny and humorous comments were made by the students watching. The chef at the house, Larry Pinette, was exceptional, and I was introduced to many new dishes and recipes of Maine. Eggs on English muffins were new to me. My roommate and other members of the fraternity were very friendly and helpful. For example, when spring break came, my roommate invited me to visit him at his home in Belmont, Massachusetts. That was a great experience to meet his family and to enjoy my first ride in an airplane while my roommate was practicing flying to get his pilot’s license.

As the season evolved, more snow came; eventually, the snow was so extensive that the walkways on campus were like tunnels of ice, stacked along the side and obscuring views across the lawn of the quad. I enjoyed the courses, particularly microbiology. Professor Howland was a young researcher Ph.D., and I remember he would always bring his dog to sit in front of the classroom while he gave his lecture. On the weekends, the fraternity culture organized parties and invited girls from the nearby colleges to join. There was a lot of beer drinking at these parties, as we expect in colleges. The all-male school at the time was able to solve the lack of females problem by inviting girls every weekend from the nearby schools.

I was treated to my first ice hockey game at Bowdoin. They played MIT and beat them while chanting MITKEY MOUSE, Mickey Mouse. My son Mark later graduated from MIT. I was also introduced to sailing for the first time on the Atlantic ocean at the Leighton Sailing Center near the school. We would go out on the weekends and enjoy sailing the calm waters along the coast of Maine.

One of our missions on this exchange was to educate the people we met. We did this in addition to the encounters we had at the college. We also traveled around the state of Maine, visiting churches where we presented the southern perspective on the civil rights revolution that was occurring. We were well received by members of these churches. The people we encountered were universally friendly to us. We were certainly curious to the people there because there were very few African-Americans living in the state of Maine at that time. We heard reports later that the Bowdoin students, including Charlie Toomajian (later Registrar and Dean at Williams College), who went to Atlanta became active in the civil rights movement. While there, they experienced great animosity, angry threats, and racial epithets from whites in Atlanta who saw them uniting with black students in trying to integrate the lunch counters. One of those Bowdoin students was Carl D. Hopkins, who later became Professor of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University. We were transformed by our experiences in New England, and the Bowdoin students were transformed by their experience in the Jim Crow South. This exchange program was an awakening for all of us.

Those bitter cold nights heading out to the library informed my mission as a student to get the most from my education, to provide me with tools to succeed in the world. Bowdoin offered me this challenge and opportunity. This was my first experience of going to school with students from other ethnic groups. Intrinsic to that was getting to know them as people and friends. Growing up in the South during the Jim Crow era precluded that possibility. A friend I met at the time was Don Krogstad, who later graduated from Harvard School of Medicine and became a Professor of Tropical Medicine at Tulane University, specializing in malaria research. I also met Hiroki, a Japanese exchange student who I later visited at his home in Osaka, Japan. My experience during that first semester at Bowdoin led me to become the only exchange student to spend a year at Bowdoin when I returned for the second semester of my senior year. The Morehouse student that traveled with me to Maine that second semester was Matthew Thomas. I was hosted by the Delta Sigma fraternity that second semester.

Another experience at Bowdoin that resonated was my joining an intramural debating team that gave me valuable experience in speaking and conveying convincing arguments on either side of a proposition. Another skill I learned at Bowdoin was from a lifesaving course in swimming. The coach was very rigorous in the training as we went through all the basic routines of lifesaving. I became certified as a lifeguard, and it gave me the impetus to pursue swimming as a lifelong routine that strengthens one’s health.

One of my favorite places to study when the library closed was the top-floor lounge in the Senior Center (Coles Tower). There I would study most of the night, and I would crash on one of the sofas there. When I woke up, I could see the sunrise over the Atlantic Ocean. That was a breathtaking morning experience to see that view. In that lounge, I met a guy who was spending his time there writing a book. He was always typing away. His actions reinforced an idea I had previously that I could write a book one day. This student was able to manage his course load as well as work on his book as a separate project. He also discussed how he could earn a good living panhandling for money in the New York City subway system; he was an example of the very interesting students that I met. I learned to hitch-hike at Bowdoin. Fearlessly, I hitch-hiked to Boston routinely, and during spring break my senior year I hitch-hiked to Montreal, Canada. Hitch-hiking was deemed safe in 1964. In Montreal, I found a fraternity house at McGill University that generously gave me room and board during that visit. Believe it or not, hitch-hiking was common and safe in the 1960s.

I am very thankful to the students who were inspired to initiate this exchange program. This thanks also goes to the administration of both colleges for trying this experiment. The experiment that lasted until 1967 had successful results in my view. There is no question that the exchange has had an enormous impact on my life and the lives of all those who experienced the exchange at both colleges. Less than 50 students from both colleges experienced this exchange program. I would suggest strongly that this program should be reestablished in the 21st century at Bowdoin, Morehouse, and other colleges in different parts of the country. People to people friendships would emerge. There’s much to be gained from exchanges that we have learned and established. Enlightened leadership would recognize the value in such a program. I would gladly be an advisor to such a restarting of the exchange program. I observed an interesting practice at Bowdoin that was borrowed from England. On the final lecture of any course, the students would stomp their feet collectively on the floor in a practice called wooding. I appeal to both schools to restart the exchange program between Morehouse and Bowdoin College forthwith.

References

- Looking back to move forward: Bowdoin’s first attempt at integration … https://bowdoinorient.com/2018/02/23/looking-back-to-move-forward-bowdoins-first-attempt-at-integration/

- Audio of Dr. ML King’s speech at Bowdoin in May 1964 https://www.bowdoin.edu/mlk/#video

- Dr. ML King’s Visit to Bowdoin College http://community.bowdoin.edu/news/2017/01/50-years-later-martin-luther-king-jr-speaks-at-bowdoin-in-1964/

- Morehouse-Bowdoin Exchange Program https://sca.bowdoin.edu/afam50/inception/nggallery/image/morehouse-students/

- Eleven Speeches by Dr. Martin Luther King http://wmasd.ss7.sharpschool.com/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=8373388